The Land of Unequal Opportunity (Pt. 3): The Path Towards an Equitable Housing Market

Welcome to the final installment of The Land of Unequal Opportunity. In part 1 and part 2, we looked to the past to understand how government policies like redlining laid the foundation for a deeply unequal housing and real estate market, leading to segregated metropolitan cities across the US.

Problematic government policies and widespread racial bias across the finance, real estate, and mortgage industries have made it increasingly difficult for Black Americans to own homes, without which it has been impossible for Black families to accumulate wealth and achieve social mobility to the same extent as their white peers. This has resulted in a staggering racial wealth gap that only promises to widen, unless drastic action is taken.

In 2017, the black homeownership rate (41.8%) was the lowest of all racial and ethnic groups.

Between 2000 and 2017, the black homeownership rate dropped 4.8 percentage points — a loss of about 770,000 black homeowners — while the homeownership rates of other racial and ethnic groups either remained constant or increased.

The 30+ point percentage gap between black and white homeownership has not decreased since the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. The gap has actually widened over the last two decades, as Black homeowners experienced financial losses at a much higher rate than white homeowners in the wake of the housing crisis.

As Black Americans experienced a disproportionate increase in unemployment and subsequent home equity losses after the housing crisis, the racial wealth gap widened, in large part, because the Black-white homeownership gap has widened.

Profit-driven inequality

Part of the reason the Black homeownership gap is so hard to fix is that it’s grounded in a mismatch between profitability and public interest. The federal government’s role as a regulator has been undercut because it has taken a hands-off approach to developing, building, or managing any kind of real, productive housing program.

Instead, the government has left housing to the private sector. Ordinary people, particularly people of color, have not been able to secure good housing over the last century because it’s just not profitable.

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, author of Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Home Ownership, explained in an interview with Vox:

“It’s profitable to build million-dollar condos. It’s profitable to build 4,000 square foot mini-mansions. But building good, safe housing for working-class people — well, there’s no money in that… The underlying problems here are deeply structural. The government can’t effectively regulate or enforce its own rules when it has no role in producing housing, when it has essentially become dependent on the private sector to do this.”

In a different piece for The Guardian, Taylor explains how the government’s lackluster approach to housing, relegating it to the private sector, has played a large role throughout history in segregating cities and suburbs:

“ Until we remove profitability from the equation and, instead, treat the right to safe and sound housing as a human and civil right, residential segregation will continue to thrive- and, in turn, drive up prices. The higher the costs of housing, the more those who suffer from lower wages and higher debt are forced to the margins of the market… The real estate industry has always relied on racism to generate profit for its stewards. It is, quite simply, why racism continues to flourish in the housing market a half-century after the Fair Housing Act was passed. ”

The problem has become so vast that the private sector alone can’t solve it. Systemic racism can’t be fixed with a narrow solution because the problem itself is so widespread and has gotten progressively worse over the decades.

As Richard Rothstein notes in The Color of Law,

“Remedies that can undo nearly a century of de jure residential segregation will have to be both complex and imprecise. After so much time, we can no longer provide adequate justice to the descendants of those whose constitutional rights were violated.”

“Our focus can be only to develop policies that promote an integrated society’s understanding that it will be impossible to fully untangle the web of inequality that we’ve woven.”

Closing the homeownership and racial wealth gaps will require an expansive, multi-faceted approach. Untangling that web starts with government policy. In this piece, we will discuss how federal, state, and local policies should lead the charge to desegregate America; we will also discuss what must happen beyond policy to make the housing market more equitable and accessible for all.*

Policies to narrow the racial homeownership gap

The road forward, then, is paved by government policy. Let’s take a look at how policies at the federal, state, and local levels can be the foundation for building a more equitable, anti-racist housing industry.

Down-payment assistance programs (DPAs)

Saving for a down payment on a home is, for many would-be Black homeowners, the biggest barrier to entry.

In Urban Institute’s 2018 report, “Barriers to Accessing Homeownership: Downpayment, Credit, and Affordability”, researchers found that more than half of renters view a down payment as the major obstacle to buying a home.

Many would-be homeowners are unaware of low-downpayment mortgage options or local payment assistance programs.

And even if they did learn about down-payment assistance programs, the current outlook on DPAs by government agencies like the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reveals an implicit bias that disproportionately hurts borrowers of color.

As CBC Mortgage Agency’s head of government affairs Tai Christensen explains, HUD remains supportive of down-payment assistance… so long as it comes in the form of a gift from a family member. But HUD considers funds coming from down-payment assistance programs like The Chenoa Fund (without evidence) to be at a higher risk of default:

“They’re looking at this as some kind of risk to the mutual mortgage insurance fund, where there is absolutely no data to back up their claims. We’ve had Moody’s Analytics pull from our portfolio to analyze our loans, and they’re performing better than any of the state FHAs.”

This behavior from HUD is a prime example of the kind of unfounded biases that sustain the racial housing gap.

Christensen continues, “To say that a person getting [DPA] from a government entity because they don’t come from generational wealth is somehow different from a white kid from the ‘burbs saying, ‘Hey mom, I need ten grand to go buy a house,’ — there’s no data to substantiate the claim [that loans from DPA programs are at higher risk of default].”

In “The Transition to Home Ownership and the Black-White Wealth Gap,” Erik Hurst and Kerwin Kofi Charles argue that increasing the visibility of (and access to) down-payment assistance programs would particularly benefit young black homebuyers who are less likely to receive parental support when purchasing a home.

Alternative models for creditworthiness

Another issue suppressing Black homeownership is the fact that contemporary credit scoring models often fail to paint an accurate picture of credit-worthiness, particularly when it comes to minorities.

Black families are more likely than white families to have lower credit scores and thin (or no) credit files because of the historical structural barriers preventing Black Americans from accessing bank and credit products.

As a result, mortgage credit is significantly more difficult for Black families to obtain.

CBC Mortgage Agency president Richard Ferguson believes that if Washington wants to close the racial homeownership gap, they must first recognize that minorities’ credit profiles don’t often tell the complete story of their worthiness as borrowers.

First-generation Americans aren’t heavy credit users and the credit sources that they rely on —credit cards and finance companies, namely — can wreak havoc on FICO scores.

Ferguson argues that for a federal loan program to truly make a difference for minorities in America, the program must include relaxed credit standards that take into account how they actually leverage credit.

Even if relaxed standards mean an increase in defaults, Ferguson argues that that is a small price to pay to move towards closing America’s racial wealth gap:

“When you look at what’s happening around the country, with the rage that’s taken place, is it worth taking a higher default rate among those communities if that’s what it takes in order to help them get on that dream of homeownership? The only way we can help them become homeowners is by loosening up credit criteria in such a way that allows them to accomplish that.”

Closing the Black-white homeownership gap will require reforms to the current housing finance system in order to serve all people and markets more equitably, and a large part of that is relaxing credit standards for loan programs encouraging minority participation in the housing market.

Anti-discrimination policies

Black Americans often encounter discrimination at every stage of the home buying process: They are more likely to receive subpar service when interacting with real estate agents and are shown fewer homes for sale or rent than whites are.

A 2003 study found that real-estate agents’ steering of residents away from neighborhoods due to their racial composition is shockingly persistent, even if illegal.

The practice showed up in up to 15 percent of tests, based on clear and explicit indications by the agent.

At the federal level, policymakers must focus on implementing policies to address and prohibit contemporary racial residential discrimination.

Increased use of fair housing testers is one way to accomplish this. Individual testers (who have no true intent to purchase or rent the home) pose as potential homebuyers or renters in order to gather information about possible FHA violations. The use of fair housing testers has shone a light on rampant discrimination in the past.

One study by the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights tested for income and racial discrimination in 70 properties in six Chicago neighborhoods. Of the 70, 30 of the properties revealed one or both forms of discrimination. HUD funds many of these exercises through the Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) and should increase the resources allotted to the program to match the prevalence and gravity of the problem.

Racism is also prevalent in the home appraisal space, where black neighborhoods are typically and woefully undervalued.

As CBC Mortgage Agency’s Tai Christensen explains:

“You are at Four Corners. You can make a left onto Martin Luther King Boulevard, and a right onto Main Street,” she says. “Somehow the same house with the same square footage, the same brick, the same studs, is worth less on the black side of town than it is on the white side of town.”

Discrimination also thrives in the finance industry and mortgage market, but we will touch on those issues specifically later in this piece.

Community-specific policies

As the Urban Institute’s 2019 report, “Building Black Homeownership Bridges: A Five-Point Framework for Reducing the Racial Homeownership Gap”, astutely points out, while housing challenges in the United States are vast, these challenges vary greatly based on location.

While federal policies can help influence state and local policies, locally developed solutions and incentives will have the greatest impact.

The best way to bridge the gaps between white and Black homeownership (and, by extension, wealth), is for local policymakers to understand the local dynamics of wealth and homeownership to understand the resources needed in that community.

Expanding affordable housing options

Over the last few decades, the high costs of land and labor have suppressed new housing construction and driven up home prices as a result.

The number of new housing starts in 2018 was below that of the 1960s when the US population was around 55% smaller than our population today.

To make matters worse, as building costs increase, a larger percentage of construction occurs at the higher end of the market which, unsurprisingly, does little to alleviate inventory shortages at the low end of the market and has the added issue of increasing prices in gentrifying neighborhoods, further suppressing Black homeownership in formerly redlined neighborhoods.

Builders simply aren’t building ‘starter’ homes like they used to, making entrance into the housing market more expensive across the board. The average square footage for new homes in 1920 was 1,048 square feet; today the average new home is 3,000 square feet.

There is much demand in all areas of the market, but the current building trends in America serve to provide supply only at the high end of the market simply because it’s more profitable.

This is an issue that the private sector alone cannot fix; policy changes must be made to stimulate construction at the low-to-mid-range of the market.

Recognizing this problem, some cities are taking steps to reform local-land use and building codes to explore factory-built housing production options like manufactured and modular housing to increase homeownership affordability and supply.

Contrary to popular belief, research shows that some manufactured homes actually appreciate at a similar rate to site-build homes. As manufactured housing has evolved, it increasingly becomes a reasonable solution to helping Black families secure homeownership.

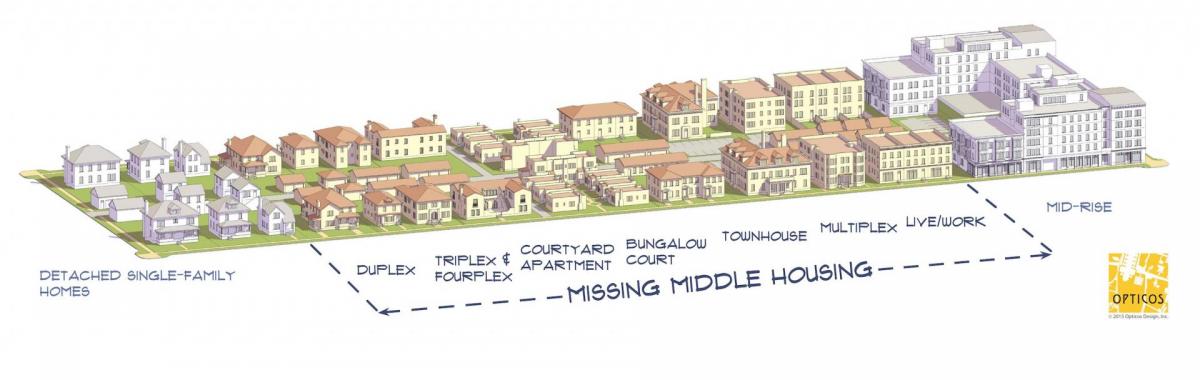

Reform zoning and land-use regulations

Restrictive land-use regulations purportedly have reduced access to affordable housing by more than 50% from 1964 to 2009.

Discrimination in the housing industry can often be disguised as income discrimination, and federal legislators should outlaw discrimination based on sources of income, in addition to supporting ‘inclusionary zoning’ policies that require developers to set aside a portion of new housing units to be affordable for low- and moderate-income residents.

Exclusionary zoning, which we touched on in Part 2, has been one of the loopholes that local governments have relied on in the past to discriminate against minorities and prevent their participation in homeownership.

In “The government created housing segregation. Here’s how the government can end it,” Richard D. Kahlenberg and Kimberly Quick argue that “policymakers should enact an Economic Fair Housing Act—to parallel the 1968 Fair Housing Act—to curb exclusionary zoning laws (such as banning apartment buildings, townhouses, or houses on modest-size lots). Just as it is illegal to discriminate in housing based on race, it should be illegal for municipalities to employ exclusionary zoning policies that discriminate based on income, which excludes the non-rich from many neighborhoods and their associated schools.”

There are also options other than complete bans on exclusionary zoning, like policies that require municipalities receiving federal infrastructure dollars to reduce exclusionary zoning policies.

For example, Senator Cory Booker’s affordable housing plan proposes that states, cities, and counties should be incentivized to develop strategies to reduce barriers to housing development and increase the supply of housing, with the opportunity to receive some $16B from HUD through a variety of infrastructure programs as a reward.

At the local level, this could look like authorizing more high-density and multi-family zoning, as well as relaxing lot size restriction. A benchmark for progress for local policies would be for affordable housing units to comprise at least 20% of all new housing stock.

Modify local tax incentives to benefit minority homeowners

Out of a desire to revitalize struggling neighborhoods, policymakers often introduce long-term tax abatement policies to entice wealthy individuals and investors to buy in the area. Under the guise of ‘improving the neighborhood’, these policies often incentivize the wealthy to live and operate in neighborhoods where they have zero obligation to contribute to the public good there, from the upkeep of streets and parks to investment in the neighborhood’s public safety or school system.

Meanwhile, the original neighborhood residents carry the tax burden of the community with no access to the tax abatements received by the wealthy.

As Richard D. Kahlenberg and Kimberly Quick argue:

“If localities believe that tax abatements are necessary for growth, they should offer them with enforceable stipulations requiring new businesses to employ, at a living wage, members of the community that host them. As well, they should offer tax abatements first to already existing small businesses to allow them to expand and employ more people.”

Policymakers often invest in neighborhood newcomers while ignoring long-term and legacy residents which, at best, leads to excluding long-term residents from self-governance and, at worst, leads to the displacement of communities of color through gentrification.

As Dorothy Brown, professor of tax law at Emory University explains,

“Tax law is a political, a social, and an economic document. So of course there are going to be racial disparities. To say, ‘the tax law is neutral’ is just nonsense.”

In 2013, for example, the mortgage interest deduction which allows filers to reduce their taxable income accounted for nearly $70B in deductions, which largely benefitted white households thanks to their disproportionate representation in the housing market.

Even the Earned Income Tax Credit, which is a tax credit often cited as a tax break to help minorities, goes half to white people.

Tax abatement programs, property tax relief programs, and tax credits for first-time homebuyers should not exclude minorities or those at the low-to-moderate end of the income spectrum, and tax incentives at the local level are an effective way to drive minority homeownership and make homeownership more accessible and affordable for those who have been historically excluded from the housing market.

Beyond policy: building an equitable housing industry from within

Because housing discrimination has had a trickle-down effect, efforts to curb racial discrimination must go beyond housing. Any policy changes made should not just seek to counter racial discrimination in housing, they must look beyond it to remedy contemporary residential racial discrimination, contemporary residential economic discrimination, and the re-segregating effects of displacement that come with gentrification.

Let’s take a look at how the racial wealth and homeownership gaps can be narrowed beyond the scope of government policy.

Better financial education

Financial literacy is an issue in America across the board, but minorities are particularly disadvantaged when it comes to financial literacy.

“Households of color are particularly fragile,” says Erin Currier, the director of financial security and mobility at Pew Charitable Trust.

“A quarter of black households would have less than $5 if they liquidated all of their financial assets.”

Because of their disproportionate wealth insecurity, thanks to centuries of discrimination, households of color have a near-impossible time building wealth and must make smart decisions with their money in order to get ahead.

As Richard Fry, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center points out, “When you have low income you spend most of your money. You use it on your basic expenses, there isn’t much to save.”

As we work to combat systemic racism from the top down, improving financial education can help Black Americans simultaneously fight economic inequality from the bottom up.

A big part of that lies in stripping away the taboos surrounding money and making the financial industry more accessible to people of color and creating programs like the Dead Day Job Army that support their specific needs.

In the mortgage and real estate markets, we must improve and expand financial education programs, including housing counseling and homeownership preparation programs for renters and younger generations.

Designing and implementing down-payment assistance and savings programs is imperative, as is increasing their visibility and making them more accessible through counseling, real estate, and lending professionals.

Likewise, enhancing overall awareness of the available state, city, county, and deferral programs would help Black households and renters who could be first-time homebuyers access homeownership.

Diversity within the mortgage and real estate industries

The mortgage industry is notorious for its lack of diversity, be it racial or gender diversity; the real estate industry is not much better.

But the demographic makeup of the country is changing. The millennial generation is approximately 44% non-white. If the mortgage industry is going to effectively serve the millennials and GenXers, the workforce must reflect these demographics.

Purchasing a home is a huge financial decision, one that would spark anxiety in even the most financially literate home buyer. Now just imagine what the process might be like for a Black homebuyer who is the first in her family to purchase a home.

Already skeptical of the financial sector (thanks to the predatory history of lenders targeting minorities with subprime loans), she walks in to meet with a white, male loan officer and looks around the mortgage lender’s office and observes a sea of white, male employees.

She will probably second-guess every single thing she’s told and every amount of advice she receives, paranoid that she might get taken advantage of. She probably has not received adequate financial education, and she may know family members who lost their homes in the housing crisis after receiving sketchy mortgage advice.

She needs the guidance of an expert she trusts, but that trust is hard to come by given the sordid history of discrimination in mortgage and real estate and the fact that the people she is looking to for advice do not share similar cultural backgrounds with her.

Creating opportunities for minorities in the housing industry, be it appraisers or loan officers or real estate agents or executives, can and should be a way to encourage Black homeownership rates and goes hand-in-hand with efforts to promote better financial education in the Black community.

“In addition to providing great jobs in a multi-billion dollar industry that’s proven largely impervious to the COVID-19 quagmire, putting people of color into positions of responsibility is sure to encourage their neighbors and other community members to approach the home buying process with confidence — or at all — a massive hurdle for families who have previously encountered racism from originators or services.”

Here at Maxwell, a key part of our ethos is the idea that making the American Dream more accessible starts with empathy. If you’re looking for guidance through your mortgage, most people want to seek guidance from someone who can understand what their life is like and what kind of challenges they face, and be able to relate to their problems.

“It makes a huge difference in communities of color, specifically young communities of color, to see like people assisting them,” Christensen says. “You’re going to feel more comfortable at a baseline level because you feel as though they understand your struggle.”

Beyond the moral obligation that we have as an industry to cultivate a more diverse workforce, there’s also a fiscal incentive.

You don’t have to look farther than New American Funding to see how beneficial diversity can be to an organization. Since its inception, New American Funding founders Rick and Patty Arvielo have placed a premium on hiring a diverse workforce and cultivating an inclusive space within the company.

As Patty Arvielo explained in one interview:

“We lack professionals that mirror our community. It’s so important to build companies that are diverse and inclusive. That’s a secret sauce at New American Funding. Anyone can build a diverse workforce with inclusive leaders at the top. I can build a large, diverse sales force because I’m Latina. I understand what they need.”

A Top 20 mortgage bank in the US, New American Funding is comprised of 58% women and 43% racial minorities. New American Funding has succeeded not in spite of their commitment to diversity but because of their commitment to it. And we could all stand to take a page out of their book as America becomes more and more racially diverse.

Responsibly expand small-dollar mortgages for purchase & renovation

From a product perspective, the Urban Institute extolls the value of responsibly expanding the availability of small-dollar mortgages for purchases and renovations as a tool to stimulate Black homeownership.

While housing prices have surpassed the 2006 peak, many houses in low-cost markets still sell for less than $70,000.

In low-cost markets, which often have a large population of Black renters, expanding access to small-dollar mortgage loans could help more Black Americans access affordable and sustainable homeownership.

Access to small-dollar mortgages could help stimulate minority homeownership in markets with affordable housing stock in stable neighborhoods like Cleveland, Ohio; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Rochester, New York; and St. Louis, Missouri.

Small-dollar mortgage programs can help renters transition to homeownership and can also help existing homeowners with renovation and repair financing to upgrade homes and build equity more quickly.

Some cities are experimenting with programs demonstrating how small-dollar loans can stimulate homeownership in under-developed communities of color. Notable examples include Baltimore’s Vacant to Value initiative to redevelop empty and dilapidated houses, or Philadelphia’s low-interest loan program to help residents fix aging homes.

Focus on driving sustainable homeownership & preservation

Part of closing the homeownership gap is encouraging new Black homebuyers. Another part of that equation is ensuring homeownership is sustainable for existing Black households.

We know Black households have lower rates of homeownership than white households, but sadly, Black homeowners are also much less likely to sustain their homeownership than white homeowners.

Urban Institute research shows that among households who bought their first homes after age 44, only 9% of white households switched to rental housing, compared with 34% of black households

Helping Black homeowners access and sustain their homeownership helps reduce the racial wealth gap by extending the wealth accumulated through home equity to future generations.

Homeownership and housing wealth is often transferred from parents to children.

Fewer Black homeowners mean fewer Black children inheriting wealth (accrued through homeownership) from their parents; according to the Urban Institute, parental wealth and homeownership explain about 12% of the homeownership gap between Black and white young adults.

Part of sustainable homeownership goes back to the financial education piece. Research shows that post-purchase counseling and third-party representation lower a homeowner’s likelihood of losing their home.

Changes to credit scoring models

Access to credit across the board has tightened in the wake of the financial crisis, and the current economic climate has only constricted things further.

In 2000, the median credit score for purchase mortgages was 692, whereas the median credit score for March 2019 was 732.

As we discussed earlier, current credit scoring models are not generally an accurate predictor of creditworthiness for minority borrowers.

Lending disparities, residential segregation, and discrimination influence credit score disparities by race that persist today, suggesting deeper systemic issues with how we assess creditworthiness.

From the policy side, loan programs to encourage minority homeownership should loosen their credit standards. But the other side of the coin is pushing for modifications to credit scoring models to more accurately reflect the creditworthiness of minority borrowers.

The current credit scoring system does not account for rent, cell phone, or utility payments into the traditional models used for mortgage underwriting.

Given the high percentage of Black Americans who rent, including rental payment history in credit scoring models and/or the underwriting process in a more standard way would go a long way towards helping Black households access credit without increasing default probability.

Use technology to eliminate algorithmic racial bias, not perpetuate it

The persistent racial discrimination experienced by minorities in America throughout the home buying process has, unfortunately, seemed to bleed over into new technology development.

Recent studies show that Black borrowers were more likely to be given high-cost mortgages during the housing market boom, and both financial technology and traditional lenders are charging higher interest rates for Black households.

“Our financial system is structured so that it disproportionally excludes borrowers of color. Technology has not improved the situation much because it has not been designed to correct inherent biases. But we can change that. We can build new technologies going forward that produce nondiscriminatory and fair outcomes. If we do not, black consumers will continue to be left out of the opportunity to build wealth.” — Lisa Rise, National Fair Housing Alliance

In March 2019, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced a lawsuit against social media giant Facebook, alleging that the platform allowed advertisers to use data in order to exclude certain racial groups from seeing home or apartment advertisements.

As we develop new technology and incorporate it into the mortgage process, it’s imperative that we are aware of our unconscious biases and how those biases can lead to algorithmic bias.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66330082/algorithim_bias_board_1.0.jpg)

If financial institutions do not serve all communities in the market, and inequities will continue; we must be aware of how our own pervasive biases, however unconscious, inform the technologies we build.

A mindful approach to building financial technology can expand responsible credit in all communities and can help make the journey towards homeownership more transparent and fair across the board.

Conclusion

It’s uncomfortable to look at our country’s dark history of racial discrimination, particularly as it relates to homeownership.

The real estate and mortgage industry has long been complicit in perpetuating inequality in housing, and while we can’t fix it all on our own, we have an obligation to drive change from within as we simultaneously push policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels to institute policies to combat the multitude of wrongs that have systematically oppressed people of color in America throughout history.

We can, and must, do better. As America becomes increasingly more diverse, the idea of the American Dream of homeownership will die unless we actively and purposefully work to combat the inequalities built into the system.

In the words of Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, “Action is the only remedy to indifference: the most insidious danger of all.”

So have the uncomfortable conversations. Tackle the tough topics. Be bold in standing against an unjust system.

If you haven’t already, it’s time for your organization to take a stance against racism and commit to building a more equitable and inclusive future, both within your organization and in the communities you serve.

The future of our industry depends on it.

*Much of this piece was built around the ideas proposed by the Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center in their comprehensive report, “Building Black Homeownership Bridges: A Five-Point Framework for Reducing the Racial Homeownership Gap.” I’m grateful to Alanna McCargo, Jung Hyun Choi, and Edward Golding for their thoughtful and nuanced work on the report, as I would not have been able to write this piece without it.

The Land of Unequal Opportunity, Part 1: A History of Redlining

The Land of Unequal Opportunity, Part 2: How Government Policy Segregated America

Sources

“3 Reasons Diversity in the Mortgage Industry Is a Win-Win for All.” Accessed July 6, 2020. https://www.homefreeusa.org/news/29.

Everyday Feminism. “4 Ways the American Dream Is Actually Just Affirmative Action for White People,” November 15, 2015. https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/11/american-dream-for-white-ppl/.

Shareable. “100 Year Timeline of Racist U.S. Housing Policy,” October 31, 2019. https://www.shareable.net/timeline-of-100-years-of-racist-housing-policy-that-created-a-separate-and-unequal-america/.

American Banker. “Bankers Need to Walk the Walk on Equality,” June 9, 2020. https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/bankers-need-to-walk-the-walk-on-equality.

Equal Justice Initiative. “Banks Continue to Deny Home Loans to People of Color,” February 19, 2018. https://eji.org/news/banks-deny-home-loans-to-people-color/.

“Bartlett et al. – Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the FinTech Era.Pdf.” Accessed July 6, 2020. https://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/morse/research/papers/discrim.pdf.

Bartlett, Robert, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace. “Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the FinTech Era,” n.d., 51.

Bayer, Patrick, Fernando Ferreira, and Stephen L. Ross. “What Drives Racial and Ethnic Differences in High-Cost Mortgages? The Role of High-Risk Lenders.” The Review of Financial Studies 31, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 175–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx035.

Booker, Cory. “Cory’s Plan To Provide Safe, Affordable Housing For All Americans.” Medium, July 26, 2019. https://medium.com/@corybooker/corys-plan-to-provide-safe-affordable-housing-forall-americans-da1d83662baa.

Bouie, Jamelle. “Opinion | The Racism Right Before Our Eyes.” The New York Times, November 22, 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/22/opinion/racism-housing-jobs.html.

Oyez. “Buchanan v. Warley.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/245us60.

“Chicago_briefing.Pdf.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.prrac.org/projects/fair_housing_commission/chicago/chicago_briefing.pdf.

Coates, Story by Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

Goodman, Laurie, Alanna McCargo, Bing Bai, Edward Golding, and Sarah Strochak. “Barriers to Accessing Homeownership Down Payment, Credit, and Affordability – 2018.” Urban Institute, September 19, 2018. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/barriers-accessing-homeownership-down-payment-credit-and-affordability-2018.

“Housing Discrimination in the United States.” In Wikipedia, March 16, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Housing_discrimination_in_the_United_States&oldid=945912982.

“Housing Segregation in the United States.” In Wikipedia, June 13, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Housing_segregation_in_the_United_States&oldid=962255221.

Redfin | Real Estate Tips for Home Buying, Selling & More. “How Redlining Caused a Wealth Gap and Low Homeownership for Black Families,” June 11, 2020. https://www.redfin.com/blog/redlining-real-estate-racial-wealth-gap/.

Hurst, Erik, and Kerwin Charles. “The Transition To Home Ownership And The Black-White Wealth Gap.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 84 (February 1, 2002): 281–97. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465302317411532.

Illing, Sean. “The Sordid History of Housing Discrimination in America.” Vox, December 4, 2019. https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/12/4/20953282/racism-housing-discrimination-keeanga-yamahtta-taylor.

Jarvis, Clayton. “How Minority Homeownership Can Help in the Fight against Systemic Racism in America.” Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.mpamag.com/news/how-minority-homeownership-can-help-in-the-fight-against-systemic-racism-in-america-224481.aspx.

Madrigal, Alexis C. “The Racist Housing Policy That Made Your Neighborhood.” The Atlantic, May 22, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/05/the-racist-housing-policy-that-made-your-neighborhood/371439/.

MARTINEZ, AARON GLANTZ and EMMANUEL. “Kept out: How Banks Block People of Color from Home Ownership.” mcall.com. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.mcall.com/news/pennsylvania/mc-nws-racial-discrimination-home-loans-redlining-20180214-story.html.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press, 1993.

McCargo, Alanna, Jung Hyun Choi, and Edward Golding. “Building Black Homeownership Bridges: A Five-Point Framework for Reducing the Racial Homeownership Gap,” n.d., 15.

“Millennial Homeownership Why Is It So Low, and Ho.Pdf.” Accessed July 6, 2020. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98729/millennial_homeownership_0.pdf.

“Millennial Homeownership: Why Is It So Low, and How Can We Increase It?,” n.d., 67.

Nasiripour, Shahien. “Minorities More Likely To Be Denied Refinancing.” HuffPost, 12:01 500. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/minorities-more-likely-to_n_306870.

Nodjimbadem, Katie. “The Racial Segregation of American Cities Was Anything But Accidental.” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-federal-government-intentionally-racially-segregated-american-cities-180963494/.

HousingWire. “[PULSE] 3 Ways to Increase and Empower Black Homeownership,” March 12, 2020. https://www.housingwire.com/articles/pulse-3-ways-to-increase-and-empower-black-homeownership/.

Quick, Richard D. Kahlenberg & Kimberly. “The Government Created Housing Segregation. Here’s How the Government Can End It.” The American Prospect, July 2, 2019. https://prospect.org/api/content/7fff016a-4652-599e-84c7-968697d9aba7/.

“Racial Discrimination in Mortgage Market Persistent over Last Four Decades.” Accessed June 15, 2020. https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2020/01/racial-discrimination-in-mortgage-market-persistent-over-last-four-decades/.

“Responding to a Crisis: The National Foreclosure Mitigation Counseling Program, 2008-2018: A Capstone Evaluation | Information Resource Center.” Accessed July 6, 2020. https://ircsofia.wordpress.com/2019/03/22/responding-to-a-crisis-the-national-foreclosure-mitigation-counseling-program-2008-2018-a-capstone-evaluation/.

Richardson, Brenda. “Redlining’s Legacy Of Inequality: Low Homeownership Rates, Less Equity For Black Households.” Forbes. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brendarichardson/2020/06/11/redlinings-legacy-of-inequality-low-homeownership-rates-less-equity-for-black-households/.

Rothman, Joshua. “The Equality Conundrum.” The New Yorker. Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/01/13/the-equality-conundrum.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Reprint edition. Liveright, 2017.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. “Housing Market Racism Persists despite ‘Fair Housing’ Laws | Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor.” The Guardian, January 24, 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/24/housing-market-racism-persists-despite-fair-housing-laws.

Economic Policy Institute. “The Racial Wealth Gap: How African-Americans Have Been Shortchanged out of the Materials to Build Wealth.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.epi.org/blog/the-racial-wealth-gap-how-african-americans-have-been-shortchanged-out-of-the-materials-to-build-wealth/.

“The Road to Zero Wealth | Prosperity Now.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://prosperitynow.org/resources/road-zero-wealth.

Thompson, Brian. “The Racial Wealth Gap: Addressing America’s Most Pressing Epidemic.” Forbes. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brianthompson1/2018/02/18/the-racial-wealth-gap-addressing-americas-most-pressing-epidemic/.

“What Is Equality? Part 1: Equality of Welfare on JSTOR.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2264894?seq=1.

Williams, Dima. “A Look At Housing Inequality And Racism In The U.S.” Forbes. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dimawilliams/2020/06/03/in-light-of-george-floyd-protests-a-look-at-housing-inequality/.